About state machines

A state machine is an abstract machine that can only be in one of a finite number of states at any given time. The state machine can change from one state to another in response to some external events. The change from one state to another is called a transition. A state machine is defined by a list of its states, its initial state, and the conditions for each transition.

A State machine is a simple, yet powerful tool to build a feature in an application.

- It is predictable, so it is testable

- It is a reference you can share with your teammates to reason about a feature

- It can be described in an abstract way and then be implemented with whatever programming language

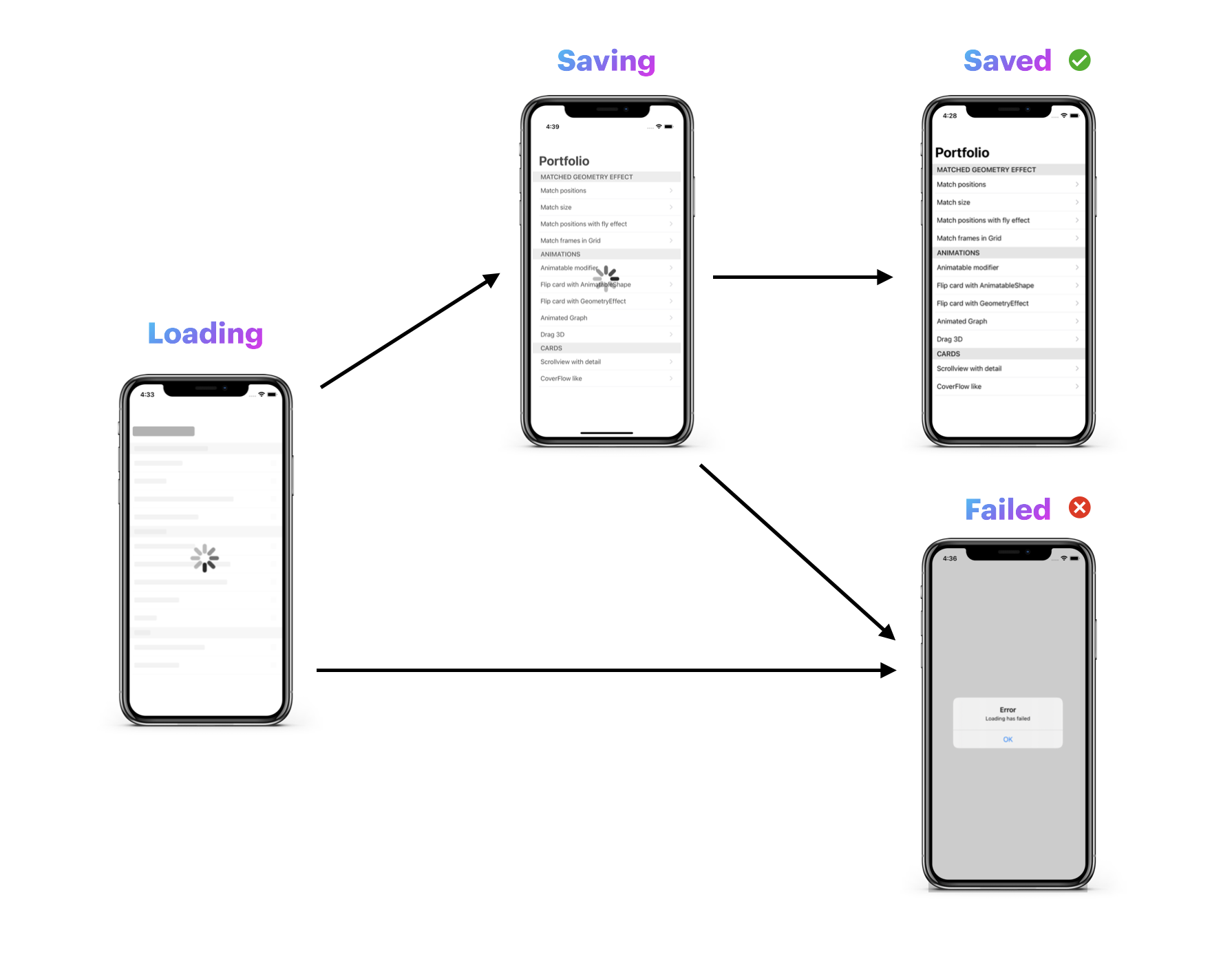

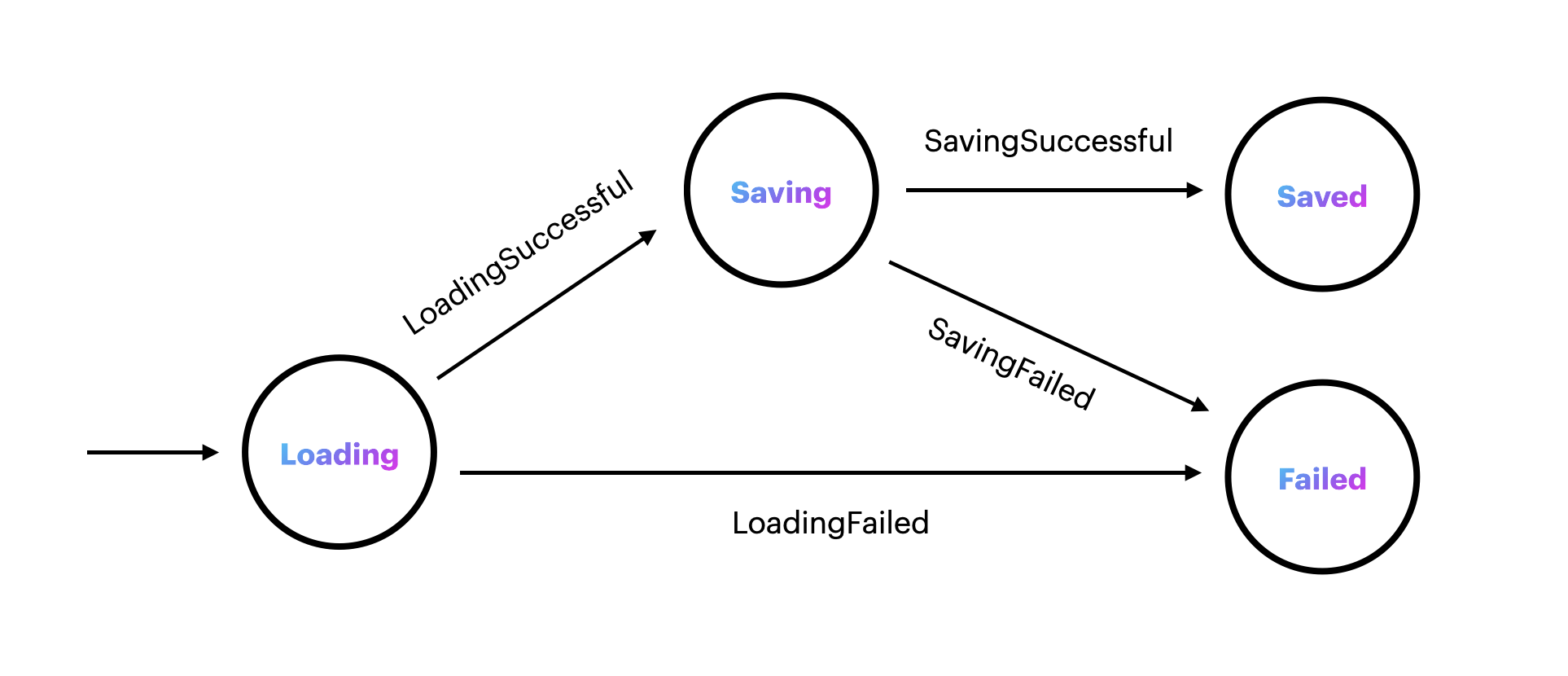

As developers, and especially mobile developers, we often have to implement features that can be summed up by the following screens:

Each screen-state has to be exclusive. We want our screens to be consistent, and to display one state at a time. A screen cannot be both Saved and Failed.

To enforce this, we can take advantage of finite state machines as they ensure that two states cannot overlap.

As you can see, the state machine matches exactly the sequence of screens we described earlier. Each new state is computed based on the current state plus an input (such as a user input or a network call result).

Lately, a lot of architectures, mostly unidirectional architectures, tend to promote “state machine like” patterns:

- MVU/ELM

- Redux

- Feedback Loops: Feedbacks, RxFeedback, Loop

Most of the time, they implement their state machines thanks to a reducer function. A reducer is a pure function that takes the current state, an event, and outputs the new state.

Here is our state machine implemented in a pseudo-code:

reducer(state: State, event: Event) -> State {

IF state = Loading AND event = LoadingSuccessful RETURN Saving

IF state = Loading AND event = LoadingFailed RETURN Failed

IF state = Saving AND event = SavingSuccessful RETURN Saved

IF state = Saving AND event = SavingFailed RETURN Failed

}

What is a DSL ?

Without DSLs, there is no World Wide Web as we know it!

A domain-specific language (DSL) is a computer language specialized to a particular application domain. HTML for instance, is a domain-specific markup language, whose domain is to describe the layout of a document displaying information. The domain of the HTML language contains concepts such as HEAD, BODY, TABLE, IMG. These keywords only have meaning within the context of the syntax defined by the HTML DSL.

We can make an interesting connection between DSLs and ontologies. An [ontology](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ontology_(information_science) describes a domain of knowledge by defining its constituting concepts and the relationships between them. There are some languages to model ontologies, such as RDF or OWL. In a way, those languages are Meta DSLs, as they offer generic syntaxes to define a domain. We could say that a DSL is a concrete implementation of an ontology.

There are several types of DSLs:

- External DSLs, such as HTML. They require an independent interpreter to be executed.

- Internal DSLs (or embedded DSL) are defined in the terms of a host language. The great thing about them is that the language compiler will check the document to ensure it respects both your DSL and the host programming language syntax. In addition to using custom terms from the domain, you are also able to use traditional programming statements (if, else, switch, …) which will dynamically impact its interpretation.

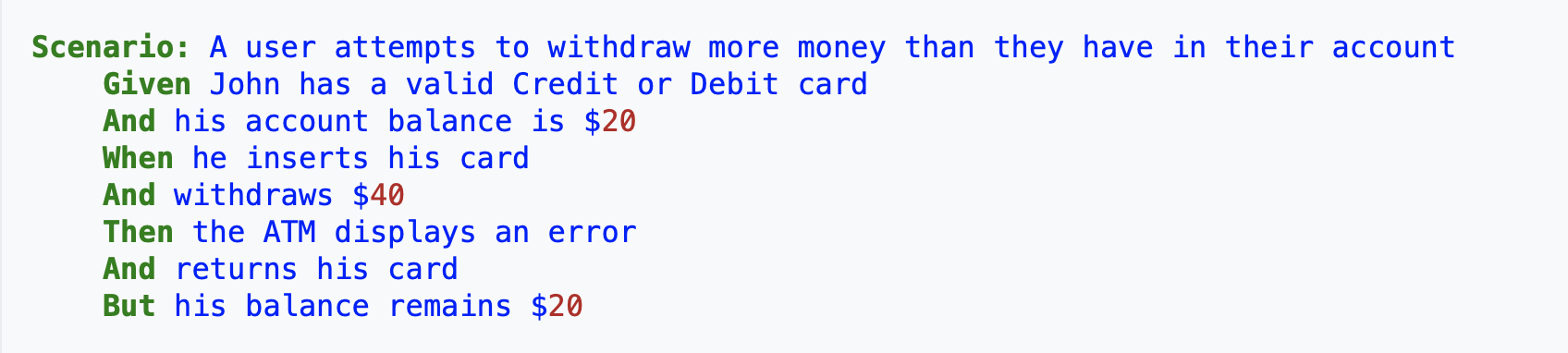

There are some famous examples of DSLs: HTLM, Gradle, SQL, SwiftUI, Gherkin.

*Here is a unit test expressed in the Gherkin DSL.

*

*Here is a unit test expressed in the Gherkin DSL.

*

Why DSLs ?

DSLs are meant for experts of a domain to be able to create content and share it without having to deal with the complexity of a fully featured programming language.

A DSL, having a syntax limited to a precise domain, can be modelled with a dedicated graphical tool and can also lead to code and documentation generation. The experts can focus on their domain from a high level perspective and still generate an optimized source code.

JetBrains MPS is a nice example of a graphical tool that one can use to elaborate and use DSLs. From a process designed thanks to a DSL, it can generate source code in programming languages such as Java, C, Javascript, etc. The code can then be integrated in an enterprise information system to execute the processes defined by the experts. This kind of tool attempts to fill the gap between domain experts and developers.

Embedded DSLs are more developer oriented, and are generally meant to provide libraries with a narrowed syntax compared to their host language.

For instance, we can imagine the previous Gherkin example being written thanks to an embedded DSL inside a Swift Unit Test.

var balance: Int?

Scenario("A user attempts to withdraw more money than they have in their account") {

Given("John has a valid Credit or Debit card and his balance is 20$") {

balance = 20

}

When("John withdraws 40$") {

balance -= 40

}

Then {

Error("The ATM displays an error") {

ATM.Error.notEnoughCredit

}

Result("The balance is still 20$") {

balance == 20

}

}

}

Under the hood, this DSL will be translated into XCTest related code.

One advantage of embedded DSLs for languages like Swift and Kotlin is their very similar syntax which allows for sharing ideas and implementations, and also for the ease of cross platform reviews.

Modeling state machines with a DSL

State machines have fairly simple concepts such as: State, Event, Transition. The resulting DSL should be pretty easy to implement, at least from a syntax perspective.

Nevertheless, implementing a finite state machine DSL might come with some challenges regarding the Swift type system, as “finite” implies to restrain the number of possible states.

Algebraic Types

In order to pick the appropriate type to model a State, we first need to understand algebraic types.

In computer science, algebraic types are data types that can be composed of other types. Usually, algebraic types are split into two categories: product types and sum types.

Product types can contain several fields, and the number of different values for this type is the product of the possible values of each field. In Swift, Struct is an algebraic product type.

enum Letter {

case A

case B

...

case Z

}

enum Number {

case 1

case 2

...

case 10

}

struct Reference {

let letter: Letter

let number: Number

}

let ref1 = Reference(letter: .A, number: .1)

let ref2 = Reference(letter: .A, number: .2)

...

let ref260 = Reference(letter: .Z, number: .10)

As you can see, the number of possible values for the Reference type is equal to the product of all the possible values of its fields: 26 x 10 = 260.

Sum types, aka “tagged unions”, stand for types that can have one value at a time among a finite set of possible values. The numer of different values for this type if the sum of all its possible exclusive values. In Swift, Enum is an algebraic sum type.

enum Reference {

case letter(Letter)

case number(Number)

}

let ref1 = Reference.letter(.A)

let ref2 = Reference.letter(.B)

...

let ref36 = Reference.number(.10)

As you can see, the number of possible values for the Reference type is equal to the sum of all the possible values of each case: 26 + 10 = 36.

What does it mean regarding states ?

In order to implement a finite state machine, we need the states to have a finite number of values, and we need them to be mutually exclusive. In other words, we need them to be represented by sum types, let’s see why.

Product types are bad candidates as they allow to mix incompatible values. For instance:

enum MyError {

case network

case database

case filesystem

}

struct MyState {

let error: MyError?

let value: Bool?

}

let state1 = MyState(error: nil, value: nil)

let state2 = MyState(error: nil, value: true)

let state3 = MyState(error: nil, value: false)

let state4 = MyState(error: .network, value: nil)

...

let state12 = MyState(error: .filesystem, value: false)

Using MyState as a struct could lead to inconsistent behaviours since it can be simultaneously an error and a valid value. There are 4 x 3 = 12 fuzzy possible states.

On the other hand, sum types are much more restrictive:

enum MyState {

case error(MyError)

case value(Bool)

}

let state1 = MyState.error(.network)

...

let state5 = MyState.value(false)

Using MyState as an enum allows only: 3 + 2 = 5 possible mutually exclusive states.

But there is an issue with enums

When designing a DSL, one of the main goals is to provide a simple, yet expressive syntax. You want it to be as close as possible to natural language. If we had to define the transition between a saving and a saved state, we could want to write something like:

enum MyState {

case loading

case saving(data: Data)

case saved(data: Data)

case failed

}

enum MyEvent {

case loadingSuccessful(data: Data)

case loadingFailed

case savingSuccessful(data: Data)

case savingFailed

}

Transition(from: MyState.saving(let data), on: MyEvent.savingSuccessful, then: { data in

return MyState.saved(data)

})

The problem with this code is that MyState.saving(let data) won’t even compile since extracting an embedded value must occur in the context of a pattern matching (switch, if case let). We could include some pattern matching in this DSL, but it would make it pretty ugly to read:

Transition(

from: { state in

guard case let .saving(data) = state else { return nil }

return data

},

on: MyEvent.savingSuccessful,

then: { extractedData in

guard let data = extractedData else { return MyState.failed }

return MyState.saved(data)

}

)

If I had to use a DSL, I would not want to use this one.

We need a type that can embed values and at the same time provide a unique identifier for each state and event.

What if we use structs to model our states/events, and leverage the struct type as a unique identifier ? After all, concrete types can be considered as mutually exclusive in the set of all possible Swift types. If you are familiar with Kotlin, it looks a lot like the sealed class concept.

struct Saving { let data: Data }

struct Saved { let data: Data }

struct SavingSuccessful { let data: Data }

Transition(from: Saving.self, on: SavingSuccessful.self, then: { state, event in

Saved(data: event.data)

}

// or even shorter:

Transition(from: Saving.self, on: SavingSuccessful.self, then: { Saved(data: $1.data) }

It looks definitely better.

My point here is to not assert that one type is better than others to model a state/event concept in a state machine. Each type has its pros and cons. For instance, Pointfree has released a library to deal with enum’s embedded values as keypaths. That could make enums good candidates to be used in a state machine DSL, while keeping a nice syntax.

I made the choice to use struct’s type as an identifier because it fits the need of state machine DSL without depending on a third party library; moreover, structs are compatible with pattern matching, which will be helpful to interpret the current state of a system when we need it.

Result builder

Now that we’ve chosen the data types that will model our states and events, we can design our DSL. Obviously, the chances are great that a state machine has more than one transition. The machine will be composed of several transitions or group of transitions. The important word here is: composed. As soon as an entity is composed of several sub-entities, we can leverage the builder pattern to construct the root entity.

For instance, if a state machine declares 3 transitions:

let transitions = Transitions()

.add(From(Loading.self, on: LoadingSuccessful.self, then: { ... }))

.add(From(Loading.self, on: LoadingFailure.self, then: { ... }))

.add(From(Saving.self, on: SavingSuccessful.self, then: { ... }))

.build()

// or

let transitions = Transitions([

From(Loading.self, on: LoadingSuccessful.self, then: { ... }),

From(Loading.self, on: LoadingFailure.self, then: { ... }),

From(Saving.self, on: SavingSuccessful.self, then: { ... })

])

Altough it is valid Swift, it is not a nice API, especially in the context of a DSL.

Within the Apple programming ecosystem, there is another domain that heavily relies on composition: UI frameworks, and particularly SwiftUI. We can take advantage of one of the mechanisms SwiftUI uses to provide a nice way of compositing transitions: Result Builder.

Basically, a Result Builder is just a way to aggregate several inputs and compute a result with them.

@resultBuilder

struct StringBuilder {

static func buildBlock(_ inputs: String...) -> String {

inputs.joined(separator: "\n")

}

}

@StringBuilder

var sentence: String {

"To boldly go"

"where no one"

"has gone before"

}

// all the values declared in the `sentence` definition

// will be passed to the `buildBlock` function as separate inputs, and the

// resulting value will be the full sentence:

// "To boldly go

// where no one

// has gone before"

With this kind of mechanisms we could write a @TransitionBuilder that would allow us to write:

struct From {

// wraps a state id, an event id and the transition to apply

...

}

@resultBuilder

struct TransitionBuilder {

static func buildBlock(_ inputs: From...) -> [From] {

inputs

}

}

struct Transitions {

private let transitions: [From]

init(@TransitionBuilder _ transitions: () -> [From]) {

self.transitions = transitions()

}

}

@TransitionBuilder

var transitions: Transitions {

From(Loading.self, on: LoadingSuccessful.self, then: { ... })

From(Loading.self, on: LoadingFailure.self, then: { ... })

From(Saving.self, on: SavingSuccessful.self, then: { ... })

}

// or something like

let transitions = Transitions {

From(Loading.self, on: LoadingSuccessful.self, then: { ... })

From(Loading.self, on: LoadingFailure.self, then: { ... })

From(Saving.self, on: SavingSuccessful.self, then: { ... })

}

A glance at a concrete DSL implementation

In the context of the CombineCommunity Feedbacks framework, I had to build a state machine DSL that would be integrated inside a feedback loop definition.

Here are some of the concepts I had to implement.

Types as identifier

In a state machine, transitions are identified by the pair: current state + event. As mentionned, I’ve decided to use the states and events types to identify them. I needed some tooling to do so:

public protocol StaticIdentifiable {

static var id: AnyHashable { get }

}

public extension StaticIdentifiable {

static var id: AnyHashable {

String(reflecting: Self.self)

}

var instanceId: AnyHashable {

Self.id

}

}

protocol State: StaticIdentifiable {}

protocol Event: StaticIdentifiable {}

As each states and each events conform to StaticIdentifiable, their type can form a unique pair when declared in a transition. All the declared transitions can then be indexed in a dictionary by this unique pair. The reducer infered from these transitions can refer to this dictionary to compute the transition to apply when receiving a state and an event.

Transitions definition

A transition is defined by a From and an On keywords in our DSL. Reading a state machine should feel natural: From the "Loading" state, On the "LoadingHasSucceeded" event, Transition to a new state.

It should also be possible to group transitions from the same state in order to allow a concise syntax:

let transitions = Transitions {

From(Loading.self) { currentState in

On(LoadingSuccessful.self) { event in

// compute new state based on currentState and event

}

On(LoadingFailure.self, transitionTo: Failed())

}

From(Saving.self) { currentState in

On(SavingSuccessful.self) { event in

// compute new state based on currentState and event

}

}

}

With this in place, we have a basic DSL to generate a state machine reducer function. The true CombineCommunity Feedbacks implementation of a DSL is very similar to what we can see here.

It also brings the concept of modifiers to the syntax (just like with SwiftUI). This lets us write things like:

let transitions = Transitions {

From(Saved.self) {

On(RefreshData.self, transitionsTo: Loading())

}

.disable {

!profile.isSuperUser()

}

}

Where the disable modifier dynamically changes the behavior of the transition. If the profile is not superUser then this transition can never be executed. The disable condition will be evaluated every time the state machine involves the pair Saved.self / RefreshData.self.

An example of usage

The Feedbacks repo contains some example applications that demonstrate the use of

a DSL written state machine in a feedback loop system.

The following system is inspired by a real life example that loads the trending gifs against the paginated Giphy API.

System {

InitialState {

Loading(page: 0)

}

Feedbacks {

// the side effect performs the network call when the state is Loading

Feedback(on: Loading.self, strategy: .cancelOnNewState, perform: loadSideEffect)

}

Transitions {

// Loading transitions

From(Loading.self) { currentState in

On(LoadingIsComplete.self) { event in

Loaded(page: state.page, data: event.payload)

}

On(LoadingHasFailed.self, transitionTo: Failed())

}

// Loaded transitions

From(Loaded.self) { currentState in

On(Refresh.self, transitionTo: Loading(page: currentState.page))

On(LoadPrevious.self, transitionTo: Loading(page: currentState.page - 1))

On(LoadNext.self, transitionTo: Loading(page: currentState.page + 1))

}

// Failed transitions

From(Failed.self) {

On(Refresh.self, transitionTo: Loading(page: 0))

}

}

}

To be fully accurate on the type of state machine Feedbacks relies on, we can speak of a Moore state machine. If we consider the side effects as the outputs of the state machine, they are determined only by the current state, whereas Mealy state machines need a pair state + input to generate an output.

Conclusion

I have not encountered many Swift implementations of state machine DSLs, especially based on ResultBuilder. There is an interesting one in Kotlin made by Tinder. It looks pretty similar to what I’ve designed (but it uses a Mealy state machine).

With the official introduction of ResultBuilder in Swift 5.4, I’m sure that DSL based projects will gain in popularity on GitHub and a commonly used pattern might emerge regarding state machines.

In the meantime, feel free to reach out to give me your feedback and ideas about state machines and DSLs.

PS: Thanks to Helene and Ryan for the review 👍🏻.