State management has become a very popular concern lately in mobile applications. The idea of a state that should be the single source of truth within an application is quite attractive ! The views would only be a displayable artefact of this state 👌.

But as you all know, with great powers comes great responsibility … and a bunch of questions 😀 :

- What the hell is a state ?

- How do I build my application around a state ?

- Is there a pattern or an architecture that ease the state management ?

- How do I leverage Swift’s type safety and value types in order to elegantly manage state mutation ?

That’s a lot to cover, but let’s not be afraid because this is pretty straightforward in the end.

This is a two parts article. In the first part I will try to guide you through the wonderful land of State and State immutability. In the second part, I will introduce RxReduce, a framework I’ve opensourced that implement a Reactive State Container Architecture.

What is a State ?

State is a notion that we find in a lot of domains: classical mechanics, quantum mechanics, thermodynamics, physics, politics, computer science, software engineering…

A few definitions from Wikipedia:

For thermodynamics, a state of a system is its condition at a specific time, that is fully identified by values of a suitable set of parameters known as state variables, state parameters or thermodynamic variables.

In information technology and computer science, a program is described as stateful if it is designed to remember preceding events or user interactions; the remembered information is called the state of the system.

In physics, a state of matter is one of the distinct forms in which matter can exist. Four states of matter are observable in everyday life: solid, liquid, gas, and plasma.

No matter the field of knowledge, a state is defined by :

- some intrinsic properties (shape, color, weight, …)

- the values of those properties at a give time

- the condition of its existence and the rules that drive its mutation

If we refer to computer science, we all learned how a state machine works. I find its definition pretty great and it brings some very good insights about what’s coming next in this post:

It is an abstract machine that can be in exactly one of a finite number of states at any given time. The state machine can change from one state to another in response to some external inputs. The change from one state to another is called a transition. An state machine is defined by a list of its states, its initial state, and the conditions for each transition.

Guess what ? An application is a state machine:

- a state for an application is the agregat of: its screens layouts, the navigation between those screens, the data it displays, the sounds it can emit, …

- it has a finite number of possible states

- it can only be in one state at a time depending on user inputs, runtime environment, physical device, external data, …

- according to external inputs (user, network, …), an application will go from a state to another (navigation between screens, view update, …): these are state transitions.

State is the heart of your application, by definition !

If State is correctly handled, you are on a good path to have a safe, bug free application.

State Container Architectures

Mastering the notion of state is only the first half of the way 😀. The challenge is to handle it well. This is where “State Container Architectures” come into play.

State Container Architectures are not a brand new idea, they all rely on well known concepts such as value types, immutability, functional programming and unidirectional data flow. Redux is a famous implementation of this kind of architecture.

Before going further, I strongly encourage you to read these 2 great articles about state container and unidirectional data flow architectures:

- iOS Architecture: A State Container based approach

- Unidirectional Data Flow: Shrinking Massive View Controllers

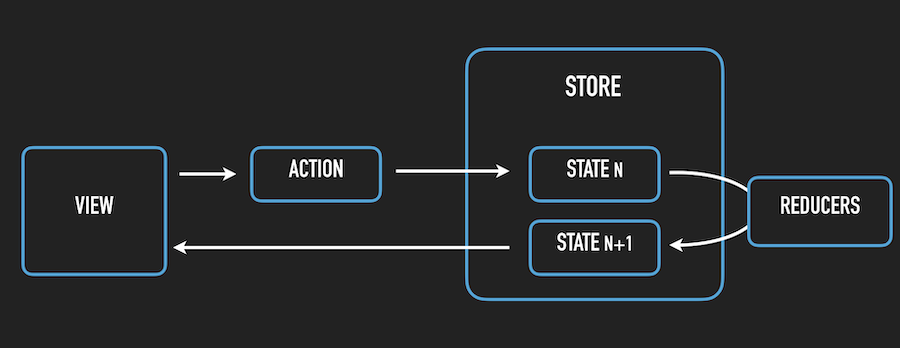

A picture worth a thousand words

The only purpose of a State Container Architecture is to provide a safe way to mutate and expose the state within your application. Here is the flow of such a pattern:

The first thing to notice here is the unidirectional aspect of the flow: you can imagine a loop of events coming from and going back to the view and producing a new version of the state at each iteration. This is our state transitions from the previous state machine definition.

A glance at each concept of this pattern

- The Store is the component that handles your State. It has only one input: a “dispatch()” function, that takes an Action as a parameter.

- The State must be immutable by definition. The only way to trigger a State mutation is to call the Store’s “dispatch()” function with an Action, it will create a new State.

- Actions are simple types with no business logic (structs for instance). They embed the payload needed to mutate the State (ids, search strings, …).

- Only pure and testable functions called Reducers can mutate a State. A “reduce()” function takes a State, an Action and returns the new State … that simple (this is the State transition).

- You can have as many Reducers as you want, they will be applied by the Store’s “dispatch()” function sequentially. It could be nice to have a R****educer per business concern for instance.

- Reducers cannot perform asynchronous logic, they can only mutate the State in a synchronous and testable way. Asynchronous work, being side effects, will be taken care of by other mechanisms (we will see that in the second part of this article).

- The Store exposes some kind of State observable so that your views can be notified each time a new State is calculated.

Why is this a nice pattern ?

As we saw earlier: “State is the heart of your application, by definition !". Having a reproductible, safe, state centric pattern brings some nice garanties:

- No uncontrolled propagation for the State modifications. As it is a value type, each mutation creates a new copy of the State. It is not a shared reference type which mutations could lead to inconsistency all across the application.

- State mutation is very strictly framed by Actions dispatching. This provides a very safe environment to onboard new players in your development team.

- Race conditions are avoided thanks to State being a value type and asynchronous works being very segregated.

- Application global State is extremely reproducible. It is an undeniable benefit of State being centralized within a Store. We can serialize it, save it on the filesystem and replay it at will. The application will be restored in a similar configuration each time.

- Not only State mutations are reproducible but also very testable because they are induced by pure functions free from side effects. All we have to test is Reducers' outputs consistency given a stable input.

I find this approach very interesting compared to the more traditional patterns, because it takes care of the consistency of your application state. MVC, MVP, MVVM or VIPER help you slice your application into well defined layers but they don’t guide you so much when it comes to handle the state of your app.

That’s it for the first part of this topic. We’ve learned a lot about the basics of State Container Architectures. In part 2, we will dive in a Reactive implementation called RxReduce that will help you handle the state, its mutations and the asynchronous work related to the side effects.

Stay tuned.