With Swift, you can define protocols by associating one or more generic types. These types are defined using the associatedtype keyword. The name “Generic Type” is a bit usurped here, we should talk about a placeholder for a reserved type. Indeed, we will see that such protocols do not offer great flexibility of use when it comes to consider them as generic.

Imagine some protocols

In the rest of this article we will rely on a simple case: A Cup is a type that can accommodate any type of Liquid. We will obviously use protocols to define these two types.

A Liquid is a protocol that exposes three properties: a color, a viscosity and a temperature (which is mutable)

public protocol Liquid {

var temperature: Float { get set }

var viscosity: Float { get }

var color: String { get }

}

A Cup is a protocol that declares using the LiquidType associatedtype. This associated type must be respect the Liquid protocol described above. A Cup exposes a simple property of type LiquidType, as well as a function to fill it.

public protocol Cup {

associatedtype LiquidType: Liquid

var liquid: LiquidType? { get }

func fill (with liquid: LiquidType)

}

Let’s implement

First of all, two types of liquids: Coffee and Milk.

struct Coffee: Liquid {

let viscosity: Float = 3.4

let color = "black"

var temperature: Float

}

struct Milk: Liquid {

let viscosity: Float = 2.2

let color = "white"

var temperature: Float

}

Then two types of cups: CeramicCup and PlasticCup. These classes are generic (to be able to accommodate any type of Liquid) and replace the associated type of the protocol Cup by a type L. By the way, we are indeed obliged to compel L to respect the Liquid protocol (as defined in the Cup protocol).

class CeramicCup<L: Liquid>: Cup {

var liquid: L?

func fill(with liquid: L) {

self.liquid = liquid

self.liquid!.temperature -= 1

}

}

class PlasticCup<L: Liquid>: Cup {

var liquid: L?

func fill(with liquid: L) {

self.liquid = liquid

self.liquid!.temperature -= 10

}

}

We now have two concrete types of Cup that can accommodate any type of Liquid.

The compiler does not like it …

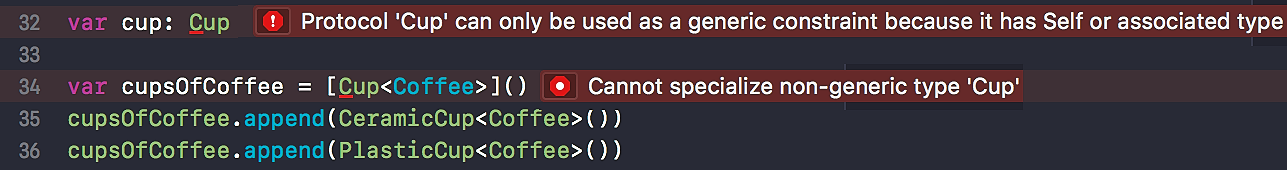

We would now be tempted to use our implementations like this:

And that’s a failure! We have all seen these kinds of creepy errors “Protocol ‘xxx’ cannot be used as a generic constraint because it has Self or associatedtype”

It is actually impossible to use Cup as a generic type. The compiler does not tolerate the unknown represented by the type associated with the protocol. It would be like solving a system of equations with two unknowns knowing only one equation.

Even if we tried to help the compiler by explicitly specifying the associated type, we would be blocked since the Cup<Coffee> notation is not even possible.

… but Design patterns do

Generic protocols will probably be supported one day if we refer to the Generics Manifesto published on the Swift Github. But in the meantime there is a trick to achieve our ends: the Type Erasure. As its name implies, it’s a technique that will allow us to erase the type associated with the protocol and make it generic. This trick may initially scare you because it is not trivial, but it only required to mechanically apply two well-known design patterns to get it done:

- Abstract class: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template_method_pattern

- Decorator: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decorator_pattern

An abstract Cup

In Swift there is no abstract class as we know it in Java. However, an abstract class is only a partial and non-instantiable implementation of a type. It is thus easy to write such an implementation of Cup. It is done by declaring a generic class respecting the protocol (just like CeramicCup or PlasticCup) but not allowing its use (the instructions fatalError prohibit us the direct use of AbstractCup)

private class AbstractCup<L: Liquid>: Cup {

var liquid: L? {

fatalError("Must implement")

}

func fill(with liquid: L) {

fatalError("Must Implement")

}

}

The first step of this technique is now reached, let’s go to the decoration.

A cool decorated Cup

If you have already used InputStream in Java, then you have used the Decorator pattern without necessarily realizing it. It is this pattern that allows a FileInputStream to be an InputStream while adding new features to it. FileInputStream will encapsulate a classic InputStream (given as a parameter of its constructor), while specializing certain behaviors. The interest of such a pattern is that you can indefinitely nest decorators without freezing the inheritance tree. This is how a BufferedInputStream can decorate a FileInputStream as well as a basic InputStream.

But back to our cups. In our case, we will build a decorator encapsulating a Cup. We already have the basic implementation of our Cup with AbstractCup (same thing as InputStream in the Java example), so we can define a wrapper (or decorator) that will inherit our AbstractCup while delegating the properties and function calls to the Cup that it encapsulates.

final private class CupWrapper<C: Cup>: AbstractCup<C.LiquidType> {

var cup: C

public init(with cup: C) {

self.cup = cup

}

override var liquid: C.LiquidType? {

return self.cup.liquid

}

override func fill(with liquid: C.LiquidType) {

self.cup.fill(with: liquid)

}

}

We can notice the constraint imposed on the Cup and LiquidType types. We must make sure that the type of liquid in the AbstractCup that we decorate is exactly the same as the one of the cup that we take in parameter in the constructor.

CupWrapper is therefore at the same time a Cup and a Cup wrapper. In a way, it allows to transform a Cup (which is only a protocol) in a concrete type. But in the end, it is still well the Cup passed as a constructor parameter that will dictate the wrapper behavior.

At this stage of the process we already have a usable result and we have made our protocol usable in a generic way:

var cupsOfCoffee = [AbstractCup<Coffee>]()

cupsOfCoffee.append(CupWrapper(with: CeramicCup<Coffee>()))

cupsOfCoffee.append(CupWrapper(with: PlasticCup<Coffee>()))

We managed to declare an array of cups of coffee. The associated type has been erased as expected.

Refinement

If we want to bring the concept of Type Erasure to an end (and in the same way that it is implemented in Swift’s standard library), we have one last step to go. I invite you to see the official documentation of the type AnyIterator (Standard Swift Library) to give you an idea of the final goal that we set ourselves.

I would first like to draw your attention to the declaration of the AbstractCup and CupWrapper classes. Everything has been done so that they are neither visible nor directly modifiable by the user of our model (final / private). The idea is to hide as much as possible the implementation of our Erasure Type pattern and to expose to the outside world only the simplest possible mechanism.

We will therefore provide a truly generic AnyCup class that will be a simple Cup wrapper. Somewhere it is a matter of applying a decorator pattern a second time directly on the Cup protocol (using under the hood our CupWrapper to delegate the work):

final public class AnyCup<L: Liquid>: Cup {

private let abstractCup: AbstractCup<L>

public init<C: Cup>(with cup: C) where C.LiquidType == L {

abstractCup = CupWrapper(with: cup)

}

public func fill(with liquid: L) {

self.abstractCup.fill(with: liquid)

}

public var liquid: L? {

return self.abstractCup.liquid

}

}

Et voila …

It gives us something quite simple and intuitive to use:

var coffeeCups = [AnyCup<Coffee>]()

coffeeCups.append(AnyCup<Coffee>(with: CeramicCup<Coffee>()))

coffeeCups.append(AnyCup<Coffee>(with: PlasticCup<Coffee>()))

coffeeCups.forEach { (anyCup) in

anyCup.fill(with: Coffee(temperature: 60.4))

print(anyCup.liquid!.color)

print(anyCup.liquid!.temperature)

}

var milkCups = [AnyCup<Milk>]()

milkCups.append(AnyCup<Milk>(with: CeramicCup<Milk>()))

milkCups.append(AnyCup<Milk>(with: PlasticCup<Milk>()))

milkCups.forEach { (anyCup) in

anyCup.fill(with: Milk(temperature: 30.9))

print(anyCup.liquid!.color)

print(anyCup.liquid!.temperature)

}

The line of code that was causing us a problem:

var cupsOfCoffee = [Cup<Coffee>]()

becomes:

var coffeeCups = [AnyCup<Coffee>]()

The bet is won.

Personally, I still struggle today with the use of such a mechanism because it is really not so trivial and I have to re-read it several times to be sure to understand it well :-) But if we apply mechanically enough the steps I have just outlined, one is sure to arrive at the expected result, hoping not to have to write it for too long.

The code is accessible on my Github: Playground Type Erasure

I hope this can be helpful..

Bonus

We can even add a little helper function to the Cup protocol:

extension Cup {

func toAnyCup () -> AnyCup<LiquidType> {

return AnyCup<LiquidType>(with: self)

}

}

This is a nice shortcut that can be used this way:

var coffeeCups = [AnyCup<Coffee>]()

coffeeCups.append(CeramicCup<Coffee>().toAnyCup())

coffeeCups.append(PlasticCup<Coffee>().toAnyCup())

pretty nice :-)

Stay tuned.

[Update 2019-05-11]

As I needed to setup “type erasure” for one of my professional project, I remembered a solution based on closures. I wanted to share it here as it is a very simple and elegant pattern.

A quick reminder of the protocols we had to “type erase”:

public protocol Liquid {

var temperature: Float { get set }

var viscosity: Float { get }

var color: String { get }

}

and

public protocol Cup {

associatedtype LiquidType: Liquid

var liquid: LiquidType? { get }

func fill (with liquid: LiquidType)

}

Instead of creating an abstract Class and then a wrapper holding a reference on a type conforming to Cup, we can directly build a generic wrapper Class that will keep some references on the Cup’s behaviors.

public class AnyCup<LiquidType: Liquid>: Cup {

// inner mechanism to "remember" the behavior of the cup

// passed in the init function

private let fillClosure: (LiquidType) -> Void

private let liquidClosure: () -> LiquidType?

init<CupType: Cup>(with cup: CupType)

where CupType.LiquidType == LiquidType {

self.fillClosure = cup.fill

self.liquidClosure = { return cup.liquid }

}

// conformance to Cup protocol

public var liquid: LiquidType? {

return self.liquidClosure()

}

public func fill(with liquid: LiquidType) {

self.fillClosure(liquid)

}

}

You can see it as some kind of delegation mechanism. As we cannot keep a reference on a Cup because of its associated type, the wrapper keeps references on the Cup’s functions and properties and is responsible for their execution.

Pretty straight forward 👍.